Week 2: Land Management Priorities

This week’s Denali Discussion Forum explored the management practices that residents thought could address the benefits and threats highlighted in Week 2 (January 18-22). Participation in this week’s exercise was high, and similar to last week, there has been tremendous enthusiasm and interest expressed. We have noticed that some perspectives are converging while others are maintaining unique directions. These similarities and differences are exactly what we would hope to see! We would like to commend everyone for maintaining a respectful tone and showing a clear interest in learning from one another. We developed this summary sheet to share what we have observed from your posts. We would very much appreciate hearing your feedback online or by email in response to this material.

Priorities of Management Practices

Week 2 Prompt: What are the public land management practices you think will best support the benefits you associate with the landscape? How should management practices change to reduce the threats facing the Denali landscape?

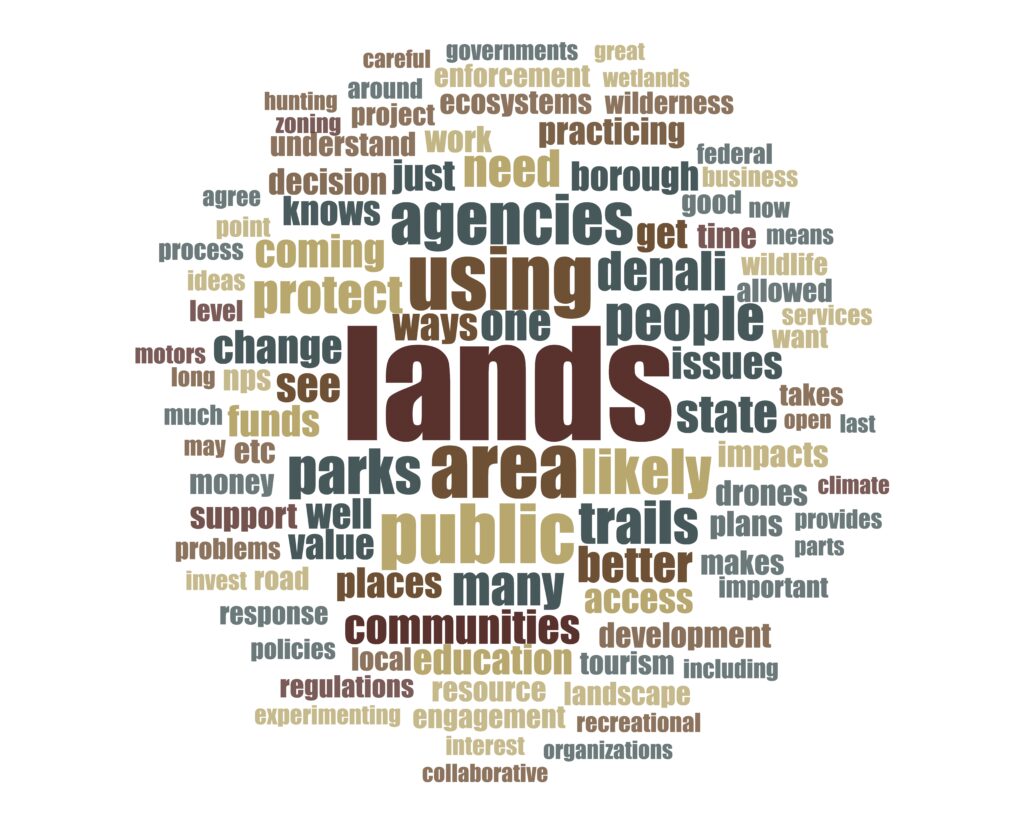

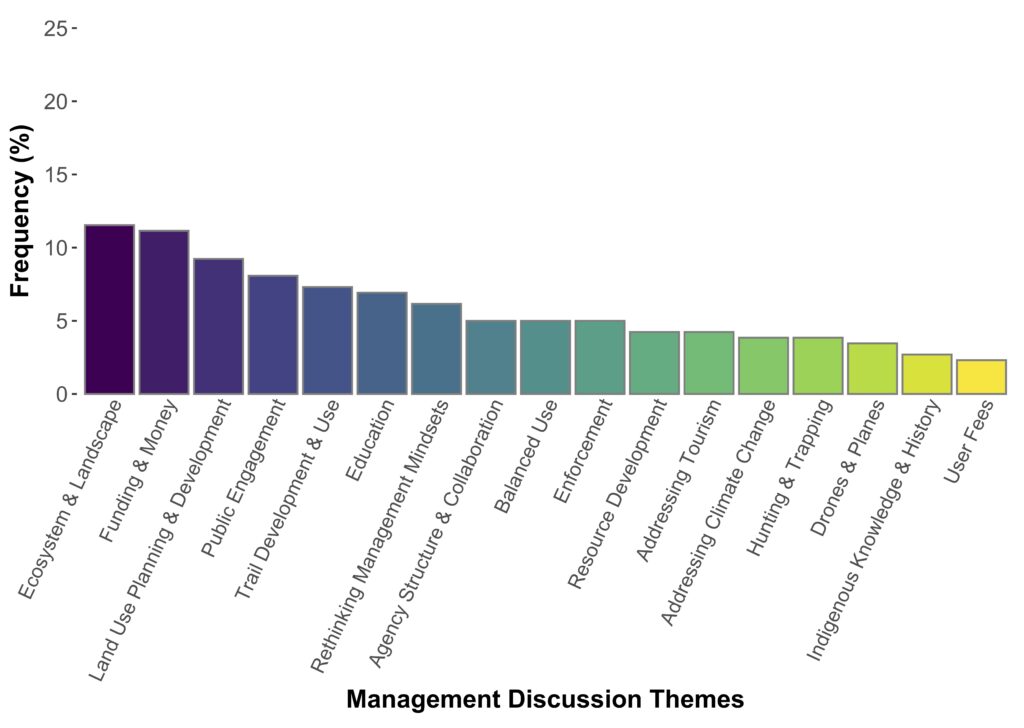

There was an array of management practices discussed in Week 2 (Figure 1), which built on what was shared at the beginning of the Denali Discussion Forum. A total of 17 broad themes related to management practices were identified in Week 2, in addition to 12 management practice themes that were discussed in Week 1. Across the three groups of residents, you perceived similarities in the role of formal regulations, management practices specific to resource development, and the framing of key issues being prioritized by land management agencies. The most popular management practices discussed across all three groups were ecosystem and landscape-level planning, issues of funding, and formal regulations to guide human development and land use. Group A discussed how to better enforce existing regulations, as well as had an important discussion about supporting meaningful public engagement. Group B discussed the importance of better collaboration amongst land management agencies and other stakeholder groups, especially in the context of supporting landscape-level planning. Group C talked about funding priorities based on money and how to recenter management strategies to support the intrinsic values of the landscape versus economics and other anthropocentric benefits.

Some of you noticed that the prompt for Week 2 was relatively broad. This approach allowed us to learn about the management practices most relevant for you, in addition to how you talked about which practices are prioritized, why they are implemented, and how they are discussed. We organized your posts across the prominent topics of conversation, from broad goals that encompassed a range of issues to regulations that you thought are, or should be, adopted by public land managers. One major difference between the Week 1 and Week 2 discussion was that in Week 2 there was a fairly even spread across the frequency of topics discussed (Figure 2). This highlights the complexity and variety of management practices that were deliberated.

Public Engagement and Inclusive Conservation

One of the prominent themes that emerged in Week 2 focused on meaningful community engagement—and how this might be improved—for public land management in the Denali region. In general, all three groups shared a number of ideas about how to leverage community-based programs to have a larger influence on public land management and called for better collaboration across stakeholder groups: “Land owners at the federal and state and borough levels need to work together, collaborate, and include scientists, indigenous people, and so forth.” However, some of you expressed frustration about the lack of respect residents receive by land managers and decision-makers in the region, because this inhibits meaningful collaboration. One resident shared how they had made multiple attempts to engage in public processes over the years that have largely been “brushed off and ignored.” Overall, there were diverse sentiments around local participation and inclusion in protected area management—ranging from positive outcomes to feelings of frustration and mistrust—but a similarity was the desire to continue improving the process for meaningful public engagement.

You posed a few questions specific to research that aims to advance the notion of inclusive conservation, such as the ENVISION project that is hosting the Denali Discussion Forum. One of you asked how your online conversations could bridge the gap between residents and public land managers, as well as how local voices were being represented across different aspects of the ENVISION project and the local Executive Committee:

“We participants are having inclusive conversations with each other, but we also need to be having inclusive conversations with the decision makers. We need more than for them to just observe our conversations. How do they plan to incorporate our multiple viewpoints into decision making about resource management?”

We very much appreciate these points. The ENVISION project was funded to understand the points of (dis)agreement among residents, listen to divergent and unheard voices, and create opportunities to represent these ideas among all stakeholders and decision-makers. One resident shared how individuals may use forums and other avenues to enact change in the future:

“Lastly, as individuals we all hold responsibility as well, to use opportunities and forums to express opinions and ideas, to listen to others and respect how their values differ from our own, to be open to compromise, but also to recognize when that turns into compromising the resource and stand tall in that moment.”

Management Practices Address Key Concerns

A wide range of management practices in the Denali region were described in Week 2 (Figure 2). You indicated these management practices were being adopted in response to preserving the environment, mitigating the effects of tourism, and sustaining growth.

Management practices related to environmental preservation

Environmental preservation was a salient concern across all groups in the Denali Discussion Forum. Although a number of ecosystems and organisms were mentioned, the protection of wetlands and landscape scale conservation were prioritized. When discussing federally designated Wilderness specifically, one of you stated, “The National Park System is for all to enjoy but the designated wilderness of Denali should remain just that, wilderness.” A range of practices were suggested as mechanisms to preserve Wilderness, including ecosystem-based management, as well as requirements that “no unmitigated wetlands destruction when a large development project occurs.” Another interesting topic discussed in the context of environmental preservation was the “right to roam” to encourage non-consumptive land uses and provide people with opportunities to explore the landscape and protect open spaces. Similarly, you proposed management practices that support balanced use, but debated how exactly to balance the needs of people and different interest groups with environmental considerations.

In Week 2, you discussed a range of issues that complicated environmental preservation, including trail development and use, drones, motorized vehicles, and hunting/trapping. One resident suggested that trails should be separated into motorized and non-motorized uses, but that new trails should be multi-use within these two categories to reduce a network of trails with discrete designated uses. A point of agreement seemed to be that the positive outcomes of trail development and use, such as providing recreation, should be considered alongside the effects of “fragment[ing] habitat for wildlife.” Drones were a hot topic in one of the groups, and some disagreement emerged around how to effectively regulate drone use. Some of you thought that drones should not be allowed within protected area borders, but others noted drones could be a less invasive tool to show people the wonders of a landscape. A less contested issue was motorized vehicles, though several of you were still frustrated that even when policies exist to regulate the use of vehicles, they are not always followed or effectively enforced.

Management practices related to tourism

One of the key concerns that was discussed in relation to management practices was industrial tourism. To manage tourism, one resident proposed the following solution based on adapting regulations to the types of tourism in the region:

“Regulations that support a small-business tourist economy over industrial tourism may be essential to ensuring the greatest local economic benefits from tourism, providing authentic experiences to visitors, and ensuring that single actors do not become so economically powerful that they can justify not abiding by environmental best practices and regulations.”

Multiple conversations in Week 1 also pertained to practices that mitigated the effects of tourism, including regulating Airbnbs, increased user fees, and restrictions based on carrying capacity. In general, user fees and/or tourism taxes were proposed as an avenue to offset impacts on the local community and environment: “Does the state have a tax [gasp!] on some tourist activities to support subsistence, education, conservation, etc? I assume not, but it would be an interesting conversation to hear.” However, some of you were opposed to the idea of user fees, especially for local residents, because fees can create a pay-to-play atmosphere that excludes non-wealthy visitors from having equitable access to the landscape.

Management practices that guide growth

Large-scale development projects, population and tourism growth, and the expansion of developed areas were all threats that you considered for the region in Week 1. In response to these threats, discussions in Week 2 considered management practices that regulate human development, specifically zoning and land-use planning. Many of you stated a general unease or dislike for formal regulations, but also acknowledged practices such as zoning that may be another way to better respond to landscape change:

“Over the next 30 years, the Denali Borough, DNR, and BLM will need to apply some zoning, codes and laws to protect the landscape and keep this area wild. No one wants to see so many rules that hinder the joys of living here, but at the same time there is a need for governance that balances protection of this area while still offering the ability to explore and enjoy the Denali wilderness.”

There were mixed feelings about formal regulations enforced by various levels of government, such as zoning, and other solutions that included community-led planning. The idea of community-led planning was a particularly popular alternative to current land use regulations:

“…I think communities really thrive when they have enough regard for themselves to say yeah, we can all work together and come up with a plan that will really improve our quality of life, even it means giving up a desire to be able to do exactly what we want, when we want, where we want…. community-led planning isn’t some big-government bogeyman, it’s a way to show that we care about each other and our home.”

Reconsidering Management Decision-making

Many of you took a step back to think about the broader goals, underlying priorities, and other external factors that may influence or constrain decision-making for protected areas versus specific practices. One resident pointed out that one way to affect change in the region was by focusing on how management practices are deliberated on, passed, and ultimately enforced:

“It seems to me that before looking at specific land management policy and practices, which I take to mean things like I noted above, one must first look at the “constraints and influences” framework that land managers are subject to, and which is a strong indicator of what policies and management guidance are likely to happen.”

You shared a range of perspectives on decision-making and offered suggestions on how the process might be improved. Money and influence, at the frustration of some of you, were brought up as two interconnected constraints in protected area management. Some of you were concerned with how “money influence outcomes disproportionately,” which ties into unequal representation in the decision-making process. Additionally, the issue of funding arose after a regulation or other formal management practice was passed. One resident summed up this challenge by stating, “What I am hearing is we have laws/regulations that don’t get any support or teeth. Or really no money…” And likewise, in a different group one of you said, “[resident a] is right about the existence of current good polices and plans but without staff and funding there is not implementation.” A concern that was raised was that even if the “right” management practices were used, there could be inequities in enforcement. One resident shared their experience with the lack of enforcement of vehicle use on a nearby trail:

“A practice that pops up for me… is the allowance of Monster trucks and track vehicles. They were banned from the Rex Trail going East several years ago… Then [motorized vehicles] all moved to the west side of the road and they just ran everything over. That isn’t legal but [officials] don’t enforce any of their regulations. Once the damages done the damage is done, and it’s not like you can just go find them after it’s over.”

In review of enforcement as part of the public land management framework, it seems that changing part of the decision-making process may involve discerning how to more effectively enforce existing practices:

“In closing, after my few years on the enforcement side, I assure you more policies, regulations, and laws are not always the panacea to our problems. A policy that would support the laws we have would make a more lasting impact in the long run.”

You also raised concerns about collaboration and manager discontinuity as barriers to the formation, implementation, and enforcement of effective management practices. There was agreement in one of the groups on what was perceived to be a revolving door of high-level management officials, who each bring a punctuated agenda. One resident voiced that continuity in leadership was an issue “Ever-changing leadership at the National Park is a problem, especially in recent years, and leadership structure generally in the Park Service is often detrimental to their ends.” Additionally, you shared that within high-level turnover, some public employees, such as bus drivers, who had been working and living in Denali for many years with an “on the ground” perspective were undervalued in their ability to help guide decision-making.

Transforming Protected Area Management

A number of best practices were highlighted in Week 2 with an eye toward transforming the way public land management agencies function in the region. These included ecosystem and landscape-level planning, funding and enforcement reform, education, and reframing land management frameworks based on intrinsic values. Landscape-scale planning was proposed as a holistic solution that considered the entirety of an ecosystem. Interconnectivity was also considered essential for mitigating and adapting to climate change. One resident suggested that management may be improved through an ecosystem services approach. However, another resident was apprehensive about this because it framed landscapes away from their intrinsic value. In comparison to landscape-level management, some of you suggested that bottom-up approaches would encourage stewardship across “many small areas versus one large one.”

The role of education in teaching people about the landscape and its history was discussed as a way to create long-term change in the region and better support a range of implemented management practices. As a support system for management, some of you suggested educational solutions such as trail signs to better communicate with visitors. There was also recognition that education could reframe tourism into an opportunity for positive change. One group discussed the importance of teaching Indigenous history for residents and visitors:

“We could teach everyone who visits about the history, the culture, the language (loss), the subsistence lifestyle, the families who’ve endured over time… For example, the elders here were whipped and scolded whenever they used their language back in the 30s and 40s, and so my generation wasn’t taught the language and it is/was a dialect of the Ahtna Athabascan language specific to the Yedatenena’ people. It seems like a lot of change for one lifetime. History is for learning from.”

Transforming Protected Area Management

Values were a clear topic of conversation in Week 2. At the beginning of the Denali Discussion Forum, one resident suggested that values could be used to establish points of agreement for protected area management: “We often agree on values (enjoyment and preservation of wilderness; quiet living), so I often begin conversations on land use by discussing values.” In another group you discussed how intrinsic and other non-monetary values should be assessed and used to support decision-making:

“I’ll end with this question: Why is a parcel of land worth more money cleared of trees than with trees? I don’t know the answer to this but I think we need a paradigm shift in how we value the land.”

Overall, your discussions about values ranged across a variety of topics, but there was a general sense that a values-based framework may be a step in the right direction for guiding management practices. Or, at the very least, that decision-makers who share the values of local residents are more likely to make land management decisions that are viewed favorably. You suggested that local values are not always reflected in the decision-making processes for protected area management in the Denali Region, and initiated a discussion on realignment of values across local communities and protected area policies.